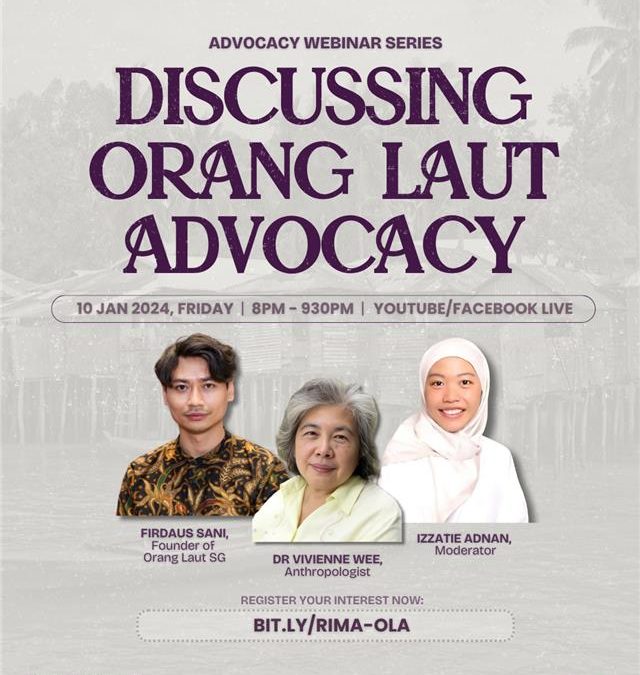

RIMA Brief – January 2025

Discussing Orang Laut Advocacy in Singapore

Speakers: Dr Vivienne Wee, Firdaus Sani

Click here to watch the Webinar

Key Takeaways

1. There is a need for the recognition and preservation of Orang Laut heritage, establishment of proper research ethics guidelines, and creation of dedicated community spaces for cultural practices and gatherings.

2. Current Orang Laut advocacy efforts include documentation of cultural practices, engagement with government bodies, educational initiatives through workshops and learning journeys, as well as creative advocacy through art forms like music, poetry weaving, and traditional fish trap crafting.

3. Some of the bigger challenges in advocacy lie in the documenting process. This include the locating of community members, as well as the reluctance from some of them to share their stories due to stigma, or because certain stories and beliefs are kept within the family and not meant to be documented publicly.

4. Effective advocacy in the Orang Laut space, as per other forms of advocacy, include cross-sector collaboration, building knowledge capacity with different stakeholders, engagement with government bodies, and consistent community involvement in development planning and decision-making processes.

5. The public can support the Orang Laut cause by directly supporting Orang Laut SG initiatives such as Hari Orang Pulau, and other public programmes; as well as through exploring academic research, looking into their own family genealogies, and engaging with recommended readings.

Background

The Orang Laut community in Singapore continues to face negative impacts from relocation. In response, there has been a growing movement to advocate for this community, which holds rich traditional environmental knowledge and cultural heritage. This webinar, the second instalment of RIMA’s advocacy series, explores the experiences and challenges of Orang Laut advocacy We examine the advocates’ intended outcomes and discuss what makes their advocacy efforts effective. This webinar ultimately aims to hold recognition for these pioneering advocacy initiatives.

In this webinar, we heard from an anthropologist, Dr Vivienne Wee, who talked about the past of Orang Laut in Singapore and the region. We also heard from an advocate, Firdaus Sani, who shared his experiences advocating for the Orang Laut community.

The Orang Laut Past

Dr Vivienne Wee noted that there has been documentation of sea people in the region that predates what is mentioned in Singaporean history textbooks, which usually takes the starting point of 1819. This starting point was when a treaty was signed between the English East India Company and Temenggong Abdul Rahman, which gave permission for a British trading post in the Temenggong’s domain, encompassing Singapore, Batam and other smaller islands. It has been documented in the record of the meeting that when the 1819 treaty was signed, there were 500 Orang Kallang, 200 Orang Seletar, 150 Orang Gelam, and other Orang Laut — presumably Orang Selat.

This document regarded these people as the indigenous inhabitants of Singapore, of which not all were land-dwellers, but instead living on boats, dwelling on both sea and land. The British 1820 map also showed place names of Orang Laut origin, which include Jurong, Ulu Pandan, Rochor, Kallang, and many others, being well-documented and remaining unchanged.

However, even before these historically significant events in relation to national narratives, the existence of sea-dwellingpeople was ubiquitous in this region. The rising of sea levels 7,000 years ago, which saw Sundaland morphing into island Southeast Asia, submerging low-lying lands, doubling coastlines and creating islands from higher lands and mountain peaks. This gave rise to three clusters of sea people –the Moken, Sama Bajau, and Orang Laut. The Orang Laut were part of a state in Temasek/Singapore from the 7th century onwards.

The kingdom at Temasek/Singapore was part of a network of autonomous port cities seeking to profit from seaborne trade between China and countries to its west. These autonomous port cities could profit from the seaborne trade, because they obtained maritime products from the Orang Laut. Ending her presentation, Dr Vivienne Wee discussed indigeneity and indigenisation. Being indigenous in Singapore means being indigenous to not just the land, but to the7,000 years that preceded the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty. This was a treaty that demarcated the region into two spheres of influence, British Malaya (including Singapore), under the English East India Company and the Dutch East Indies under the Dutch, with Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia being their successors. Many Singaporean citizens, born and raised in Singapore, undergo indigenisation because they have no other home but here in Singapore.

Orang Laut In Contemporary Times

To contextualise the Orang Laut discourse in the contemporary context, Firdaus Sani, founder of Orang Laut SG and a descendant of the Southern Islands, shared with us about his experiences advocating in the Orang Laut space. Following Dr Vivienne Wee’s historical recounts of the Orang Laut in Singaporepost-1824, there have been many drastic changes in the livelihoods of the Orang Laut, who have had to move out of the islands to make space for Singapore’s rapid national development efforts.

Challenges Faced In The Advocacy Process

However, research ethics become a concern when dealing with vulnerable communities. There have not been established guidelines for engaging with indigenous communities, which allows these communities to be susceptible to their time, resources and knowledge being taken advantage of without fair compensation. To combat this, Orang Laut SG has strived to work with a researcher from the University of Hawaii on a framework that establishes some ground rules when it comes to research on these indigenous communities. Additionally, community members are also encouraged to understand the intrinsic value of their narratives and to be selective about research requests.

Other major challenges include locating community members, which require extensive groundwork. A challenge is interviewing elderly members many have passed away or have developed dementia. Of those who are still around, a few are reluctant to share their stories, in an effort to distance themselves from their identity. This is due, at least in part, to the stigma of being different in language and belief systems, which cause them to be looked down upon, causing them to reject their identity as Orang Laut.

Further Action

The general public can get involved in events organised and hosted by various Orang Laut advocacy groups. In particular, Firdaus urges all to support Hari Orang Pulau (Islanders’ Day) in June 2025, either through supporting the fundraiser or through direct participation.

Hari Orang Pulau aims to celebrate livelihoods and traditions, as well as introduce opportunities for research — be it through cultural mapping to track descendents, assess whether descendents are still living in poverty, or measuring impacts of displacement. It is hoped that the benefit would extend beyond Hari Orang Pulau.

Dr Vivienne Wee added that there is a need for more substantial research, particularly in tracing family genealogies, instead of just grouping people under the umbrella “Malay” label. She urged all to start research within one’s own family, examining both paternal and maternal ancestors to discover indigenous roots.

Firdaus suggested that one can start to learn more about the Orang Laut community through acquainting themselves with research done by Dr Vivienne Wee, Dr Cynthia Chou as well as Chew Soo Beng’s book “Fishermen in Flats”.

Conclusion

The advocacy work for the Orang Laut community in Singapore represents a crucial effort to preserve and recognise indigenous heritage while addressing the ongoing impacts of relocation. Orang Laut SG has taken significant strides in documenting cultural practices, establishing community spaces, and engaging with various stakeholders, including government bodies and educational institutions.

The success of these advocacy efforts relies heavily on collaboration across different sectors, from community members to researchers and policymakers. While challenges persist — particularly in locating and engaging community members, and establishing proper research ethics — there are encouraging signs of growing public awareness and recognition of Orang Laut heritage.

Moving forward, continued support from the public, increased research initiatives, and sustained engagement with government bodies will be essential in ensuring the preservation and recognition of Orang Laut culture and heritage in Singapore.

Click on the link to download and read the full RIMA brief – RIMA Orang Laut Brief _ Final